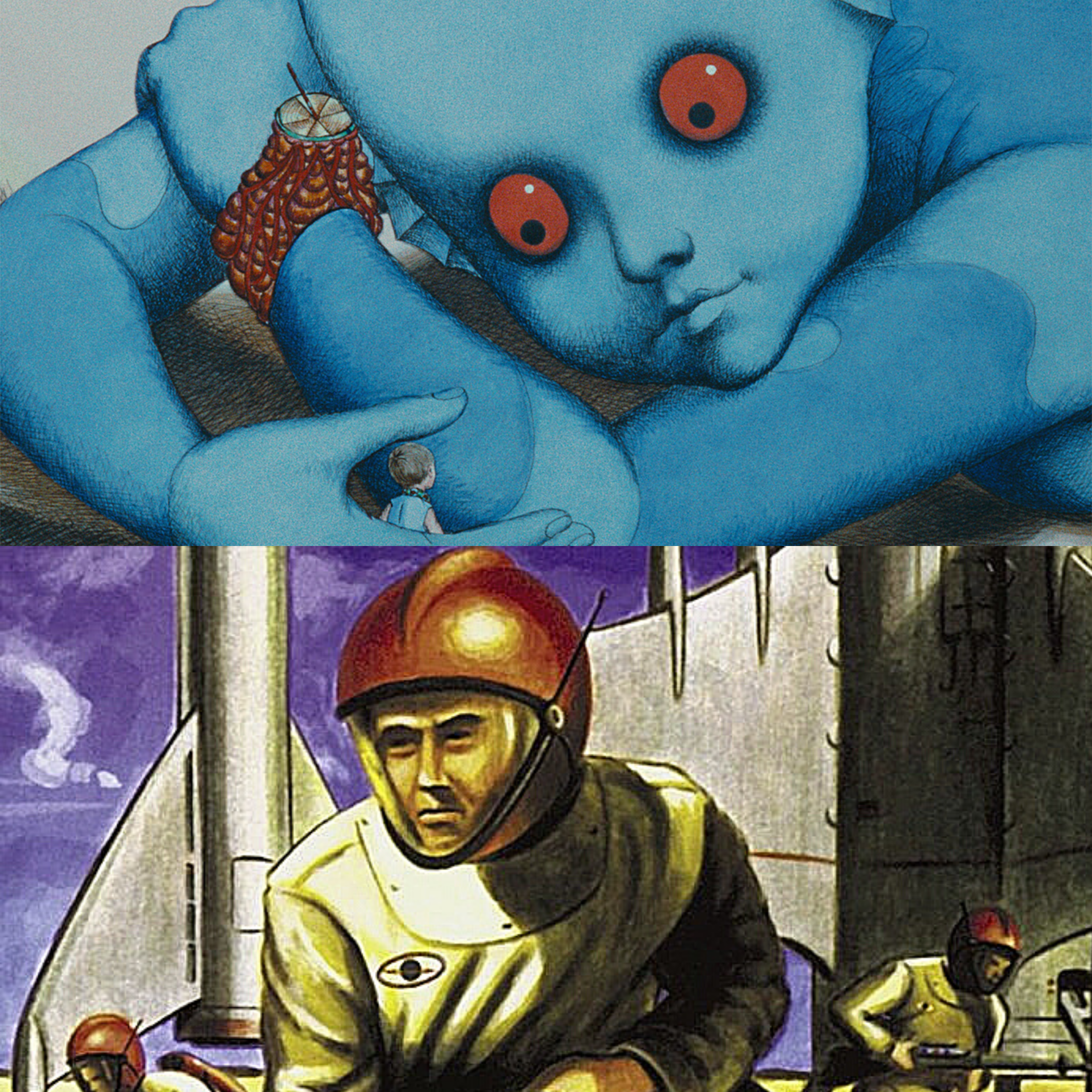

Adam Curtis’ Can’t Get You Out Of My Head + Introduction to Stranger Fiction Premium

An introduction to a series about the 2021 docuseries, Can’t Get You Out Of My Head.

An introduction to Adam Curtis & the internet

The first thing anyone who talks about Adam Curtis online will tell you is that Adam Curtis isn’t for everyone. The second is that he’s likely seen as an asset by the BBC, from whom he’s picked up a salary since long before Pandora’s Box, his first name feature in 1992. The third is likely a remark about his distinctive style – the collage of images and video, a narrative style that combines facts with his editorialising of them, the ironic juxtaposition of soundtrack and video, his use of Aphex Twin, Burial and Brian Eno tracks in his movies’ scores. You’ll be linked inevitably to this 2011 Adam Curtis parody, The Loving Trap, and be reminded once again that Adam Curtis films aren’t for everybody. That those who like his work are likely to swear by it, and that those who don’t are likely to swear at it and everyone who swears by it.

I’ll admit that my slight derision towards how people speak about Adam Curtis’s work likely stems from the fact that I fall into the first camp. With competition only from Werner Herzog (and maybe Agnès Varda), Adam Curtis is my favourite purveyor of my favourite variety of cinema – the documentary. I believe there’s no better contemporary documentary filmmaker, and this belief makes me leap at any new work by him with unbridled enthusiasm.

An introduction to Can’t Get You Out Of My Head

Earlier this week, the BBC released Curtis’s latest project, Can’t Get You Out Of My Head, a project on which he’d been working for two years. It’s his first release since 2016’s brilliant HyperNormalisation. Billed as a sort of magnum opus, the six-part, eight-hour long series deals with familiar themes for Adam Curtis fans: how did conspiracy theories grow to be this ubiquitous? Where does power rest in today’s world? Is the way we deal with the modern world’s complexities sustainable? How did the world – primarily the anglophone West, Russia, and China – get to where it appears to be in 2021: conspiracy-ravaged, anxious, uncertain?

Through tenuously woven character portraits of often ignored figures from the seventy-five years that have passed since the end of the Second World War, Curtis tells the story of new ideas and radical movements across the world: both those that failed in the pursuit of power and those that failed after the achievement of power. He profiles, for instance, Afeni Shakur and her involvement in the Black Panthers. Her son, Tupac, and his attempts to revive the Panthers. Mao’s fourth wife, Jiang Qing, and her lifelong pursuit of a seat at the table of power. Kerry Thornley, the founder of the philosophy of Discordianism, a friend of Lee Harvey Oswald’s, and the progenitor of the Illuminati conspiracy theory, which he started as a joke to spread the key idea of discordianism – that mindless skepticism of systems is the same as mindless submission to them.

Tupac is one of the characters Adam Curtis focuses on in this docuseries.

Three key themes of Can’t Get You Out Of My Head

As he paints these portraits and the events on whose periphery they found themselves, three themes clearly emerge. First, Curtis paints the post-war world as a battleground between two competing, and fundamentally incompatible, ideas – individualism and collectivism. All over the world, revolutions are spurred by ideas of a sort of shared identity, but often led by paragons of individualism, causing fissures in collectivism. Eventually the members of society at large fall prey to the mythos of individualism and the rampant consumerism that stems from it, further heightening the tensions between these ideologies.

Second, he suggests that conspiracy-mindedness is not at all new. And it isn’t a Russian invention meant to trick innocent-minded rubes into shifting allegiances from open-mindedness to regressive causes like Donald Trump or Brexit, as Twitter-based armchair progressive rebels would have you believe. In fact, this belief is itself a conspiracy theory – that millions of people can be tricked into voting entirely againsttheir best interests with their giving entirely no thought about the reality of their own lives. The fact is that an evolving world that politicians had increasingly little control over created a system of winners and losers, with the losers in the west often being hard-working working-class people, who were traditionally in a tenuous alliance with progressives from the city. It’s an alliance that’s fraying because of the lack of radical solutions from the left – the umbrella under which both the urban progressives and the rural / semi-urban working class used to once find shelter. The void that results from the failure of previously trusted systems on the one hand and the dreams of individualism on the other is quickly filled in by fear and anxiety. In a desperate attempt to feel a sense of security and belonging, people get seduced by the narratives of a shared identity from some distant past. These ghosts of the past are the third theme of the series.

Questions Curtis repeatedly asks: where do conspiracy theories come from, and how do the true and false conspiracies get mixed together?

When reality turns sour, societies are seduced by the myths of a glorious past – Britain’s guilt over the opium trade and emasculation from the fall of their empire, America’s hankering for a hypothetical historic time without the anxieties of a complex modern society, and the sudden lack of ideology after the fall of communism at the top of China and Russia (but for the ideology of money and power). Some kind of fantasy is created in the minds of a country’s populace: a vision of a past that never existed, a way of life that’s a figment of the imagination. But the myth catches on, and a significant chunk of the population comes to believe it as fact, allowing collectivism a temporary hold before individualism strikes its next blow, perpetuating the cycle. There’s a hidden question here that dovetails with people’s conspiracy-mindedness. Are people really that easy to manipulate? Or are they, as new discoveries by psychologists and neurologists suggest, harder to manipulate than previously thought?

Just purely as an experiment on societal norms, at what point would the average human bean find not crying in the cinema weirder than crying in one. How deep must the tragedy pictured be, how profound the sense of loss, how unbearable the pain of two dee characters, before your average dudebro thinks not crying would be perceived as a sign of serious apathy, psychopathy / sociopathy even.